“There were no witnesses, although a 14 year old boy in a neighboring house claimed that immediately after the shooting he saw two men, in separate cars, drive out of a church parking lot adjacent to Walker’s home.” ( Report, pg. 183 )

And that’s all the Warren Report says about Walter Kirk Coleman, the 14-year old neighbor of General Edwin A. Walker.

A loud bang

On the evening of April 10, 1963, he was working with his godfather, 19 year old Ronald Andries, building shelves in his room, when he heard a loud bang sometime between 9 and 10 pm.

In the original Dallas Police Tucker/Norvell report dated on the day of the shooting, Coleman’s location is described as “sitting in the back room of his home”. ( 24 H 39 )

A summary report submitted by Dallas Police Captain O.A. Jones dated 12/31/63, indicates that Coleman “heard a shot from his room”. ( 24 H 38 )

He ran outside and looked over a stockade fence into the Mormon church parking lot that adjoined General Walker’s property. He saw two men getting into two cars and leaving the parking lot.

One was a light green 1949 or 50 Ford and the other was a 1958 Chevrolet, black with a white stripe down the side.

More details

The next day, a follow-up interview of Coleman was done by Dallas detective W.E. Chambers.

In that interview, Coleman told Chambers that he was in a “back room” when he heard the sound and thought it was of a blowout but Andries said it was a gun shot. ( 24 H 41 / CE 2001 )

This indicates that Coleman’s reaction to the noise was not instantaneous and that he and Andries had a short conversation about the noise they heard before Coleman reacted.

He then ran out back, climbed the fence and saw a a “middle size” man “with long black hair” getting into either a ’49 or ’50 Ford light green or light blue. The Ford “took off in a hurry”.

But in this version the 1958 Chevy became an “unknown make or model” black with a white stripe.

Coleman gave no description of the man in the Chevy.

Fearing for his safety

Coleman told Chambers that his name had already appeared in the newspapers as a witness and he feared for his safety. He was so fearful that he made Chambers promise not to give the info from the interview to the papers. The Dallas Police supplied a detail officer in an unmarked car to ease the Coleman family’s worries about his safety.

Coleman’s position at the time he heard the shot and the distance of the men from the fence at the time he saw them is crucial in determining whether or not either or both men should be considered suspects in the shooting.

His changing of the description of the second car from a 1958 Chevrolet to a vehicle of “unknown make and model” just the following day, together with the concern for his safety and police protection afforded him, indicates that his life was threatened and may be the reason for that change.

In fact, he was told to keep his mouth shut.

General Walker denied access to witness

During his testimony before the Commission, General Walker accused the Commission and FBI of blocking his access to Coleman:

“…as far as I am concerned, our efforts are practically blocked. I would like to see at least a capability of my counsel being able to talk to these witnesses freely and that you or the FBI give a release on them with respect to being able to discuss it as it involves me.”

( 11 H 416 )

General WALKER. ….. I was told by others that tried to get to him that he has been advised and wasn’t talking, and that he had been advised not to talk.

Mr. LIEBELER. When was that, General Walker, do you remember?

General WALKER. Oh, it’s been at least 3 or 4 months ago.

Mr. LIEBELER. Do you know who told him he wasn’t supposed to talk to anybody?

General WALKER. No; I don’t. It is my understanding some law enforcement agency in some echelon.

( 11 H 417 )

General WALKER. ……people would like to shut up anybody that knows anything about this case. People right here in Dallas.

( 11 H 419 )

Another witness

Coleman’s description of the ’58 Chevy is verified in a June 8, 1964 FBI interview of 15 year old Scott Hansen, who was attending a Boy Scout meeting at the Mormon church on the night of the Walker shooting.

Hansen told the FBI that he saw a black-over-white ’58 Chevy in the parking lot that night and that he had seen it there on a previous Wednesday. ( CD 1245, pg. 113 )

Evidence of FBI manipulation

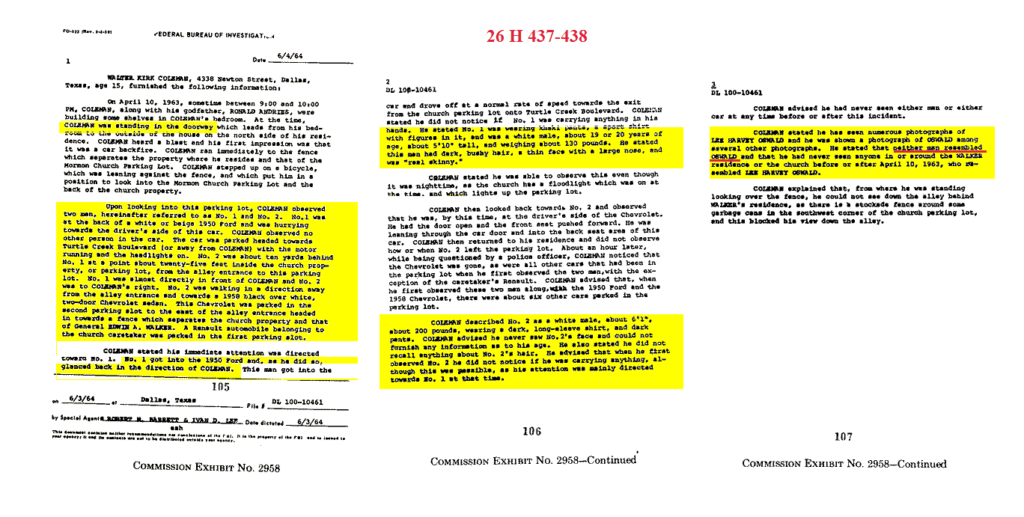

On June 4-5, 1964, ( over a year after the shooting ) FBI Agents Robert Barrett and Ivan Lee interviewed Coleman.

In that interview, the agents reported that Coleman told them that there were several “discrepancies” with the original Tucker/Norvell report.

This time, Coleman changed the color of the ’58 Chevy from black with a white stripe to black over white. He said that the Ford didn’t leave the scene in a hurry and its color was either white or light beige, not light green or light blue. ( CD 1245, pg. 117 )

In addition, Coleman gave detailed descriptions of the men he saw for the first time.

The man in the Ford glanced back at him, so Coleman got a good look at him. He described him as a white male, 19-20 years of age, about 5-10 and weighing 130 lbs with dark bushy hair, a long nose and “real skinny”. He was wearing khaki pants and a sports shirt with figures in it. ( 26 H 437 )

Coleman described the man in the ’58 Chevy as 6-1 and 200 lbs, dark long sleeved shirt and dark pants. That’s all the description he could give.

But the descriptions of what Coleman saw were not the only things that changed from the original report.

Manipulation of the Coleman’s position

The FBI report said that Coleman was “standing at an outside door at the time of the shot”. ( 26 H 440 )

The FBI needed to shorten Coleman’s response time in order to show that the two men he saw couldn’t have been involved in the shooting.

To do so, the agents measured the distance and timed Coleman in a re-enactment. The FBI found that the distance from the rear door of Coleman’s house to the stockade fence was 14 feet and it took Coleman a grand total of 2 seconds to get there. ( 26 H 439 )

The FBI measured from the alley entrance to the Walker property to the alley entrance of the church parking lot at 35 feet. It measured the distance of where Coleman said the 1950 Ford was to the alley entrance of the church parking lot at 45 feet.

That’s a distance of 80 feet, far too long for someone to have traveled in a time of 2 seconds. Likewise, they measured the distance from the 1958 Chevrolet to the alley entrance of the church parking lot at 21 feet, for a total of 56 feet, again, an impossible distance to travel in 2 seconds. ( ibid. )

On its face, the FBI report would seem to prove that the two men Coleman saw had nothing to do with the shooting, because their positions when he saw them, at 80 feet and 56 feet from the Walker property, could not have been travelled in the two seconds the FBI said it took for Coleman to get from his back door to the fence.

More than likely

But if Coleman was sitting in his bedroom, had short conversation about the noise with Andries and ran out the back door of the house, “stepped up on a bicycle which was leaning against the fence” ( 26 H 437 ) and looked over it, it’s very likely that a 12 second response time would not have been out of the realm of possibility. Such a response would have allowed a running man to travel 84 feet and been in the exact time frame with what Coleman said he saw.

If Coleman could do 14 feet in 2 seconds, a running man at the same speed could have done 80 feet in less than 12 seconds. ( 11.42 secs. )

Such timing could make both of these men suspects in the shooting.

But the FBI couldn’t have that.

On the one hand, the Commission accepted that the two men Coleman saw could not have gotten that far enough away from the fence in 2 seconds to have done the shooting, but it had no problem accepting that Oswald was able to escape the scene completely undetected in the same two seconds.

I submit to the reader that Oswald could not have vanished from behind the fence that quickly if he were “beamed up” by the starship Enterprise.

Finally, the June 1964 FBI interview of Coleman revealed that he told them that neither man he saw resembled Oswald. ( 26 H 438 )

As a result, Coleman was never called to testify for the Warren Commission.